Biking 30 years back into my past in Chester, PA

Today was the first day of my ride with the East Coast Greenway, the non-profit organization that connects communities from Maine to Florida with cycling and walking trails. Our group of forty biked along Philadelphia’s beautiful Schuylkill River Trail, the brand-new Schuylkill Banks Boardwalk, and the tranquil John Heinz National Wildlife Refuge. But the portion of today’s trip that is still rolling through my mind is our ride through the impoverished city of Chester, PA, because it’s challenging me to deal with my memories of living and working there as a twenty-year-old. Although this experience deeply shaped me as the person I became, today’s ride forced me to confront the painful fact that I have not returned to this city in nearly thirty years, thereby abandoning it in the same way that I criticized others for doing decades ago.

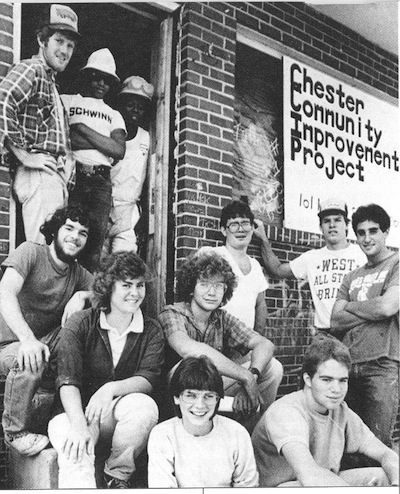

In January of 1985, I stepped away from being a full-time student at Swarthmore College and moved into the home of the Harris family on the 1300 block of West 3rd Street in Chester. For about a year, I had spent my Saturday mornings volunteering with the Chester Community Improvement Project, a non-profit housing renovation organization. The Project emerged as a partnership between the Calvary Baptist Church and the College, led primarily by Swarthmore students who were a couple of years older (and far wiser) than me. I was a relatively clueless kid from rural upstate New York who was trying to understand social change in Chester, a predominantly black and impoverished city located only a few miles from the wealthy white suburb surrounding my college. The extreme disparities baffled me, but the concept of helping urban residents to renovate and buy their own home, as a strategy for building a stake in transforming their neighborhood, appealed to my Republican roots and pulled me in. At the same time, I was pushing away from Swarthmore, a place where professors and students spoke in very abstract realms, often so quickly that my brain was not able to keep up. Working with a housing group in Chester moved me back into the realm of action, and built a meaningful sense of community and purpose with other students, where I made useful things with my hands. When I learned that the College funded a internship program, where students working full-time with a Chester non-profit organization could earn $400 per month, I leapt in head first—–with both feet—in classic high-energy, mixed-metaphor style.

I asked the Chester Project leaders to help me find a place to live in the community. The Harris family kindly welcomed me into their home on the 1300 block of West 3rd Street, right around the corner from the row house we were renovating in the photo above, a couple of blocks down from our headquarters next to Calvary Baptist Church. Mr. Harris was a deacon at the church, and Mrs. Harris raised their grandchildren and foster children at their modest home. I shared a room with Harry, their adopted son who was my age, and who, by coincidence, was the piano accompanist for the Swarthmore College Gospel Choir. Most of my time at their house was spent in the kitchen with Mrs. Harris, who taught me to appreciate foods I had never tasted (collard greens and sweet potato pie), and more importantly, talked with me as I tried to process all that was happening around me, as the only person of my race for several blocks. By living with the Harris family, walking around their neighborhood, and attending their church, I received a very personal education in Whiteness, long before I knew that concept had a name.

My work with the housing renovation project was not a “success” in the conventional sense. We did not change the neighborhood, and we staff members (all who were White twenty-somethings connected to the College) had a difficult time building true partnerships with African-American community members. While the Project continued for several years, and deeply educated several students like me, what I ended up taking away were lessons in what did not work, including some painful memories of my personal missteps, from which I wanted to walk away.

Today I pedaled through my old neighborhood in Chester, with a predominantly White group of spandex-wearing cyclists who, like me, have the financial means to take a week off from work and go exploring on our bikes. I paused to take a photo of the 1300 block of West 3rd Street, but am frustrated that I cannot remember exactly which house belonged to the Harris family. I have no address book or letters from this period in my life. I never took a photo of Mrs. Harris, nor did I keep in touch with her after moving back to the College at the end of the semester. I cannot remember her first name. In fact, after digging through the online Delaware County property records for this block and not finding any trace of them among all of the prior owners, I am starting to fear that my memories may be faulty, and begin to doubt whether I have correctly remembered the family name.

As I pedaled around the block that I walked hundreds of times years ago, very little looks the same as I remember. Calvary Baptist Church still stands on West 2nd Street, but the shape of the building does not match the one stored in my memory. Was it torn down and rebuilt, or am I imagining a different past? The block of row houses we renovated in the photo above appears to be an empty lot. Was it demolished, or did I recall the wrong location? The Commodore Barry Bridge still towers above the West side of Chester, but there was absolutely no trace of another house (or even the block) underneath it, where I spent months trying to rebuild its crumbling walls. What happened here? The answers to these questions are probably a mixture of actual urban neighborhood change over thirty years and the fluid nature of memories. But I cannot piece it together, because I kept no contact with Chester, no connection over time, and intentionally allowed those thoughts to fade away…until today.

Let’s give credit to the folks behind the East Coast Greenway, because they did not take the easy way out. It would have been so simple to design a bike path for privileged white folks that routed us only through the suburbs and avoided inner cities. Instead, the Greenway is serious about its vision to link urban, suburban, and rural communities across the Eastern seaboard. I’m proud to be part of an organization that is working to connect with Chester, rather than abandon or avoid it as so many of us have done. To be clear, this is only a bike ride, with a bunch of us white folks who look silly wearing neon jackets and spandex pants. It’s not a strategy that will bring needed social and economic change to the residents of Chester. But the Greenway brought me back, at least for part of one afternoon, to reflect on what I learned here years ago.